Returning to Ireland after the holidays is mildly discombobulating. During my time at home, as I got re-acquainted with the Metro North commute between Manhattan and Connecticut, my life in Ireland became something sort of abstract—a story to tell people as a third-person narrator. Even when the time came to re-pack my bags and return to the Emerald Isle, it didn’t necessarily feel like I was returning to something permanent. And I suppose I wasn’t.

In a way, I feel like I am floating. My roots are not fully planted in one place. My apartment, my work, and my daily life are in Dublin. But my family, my friends, my culture, and likely my future are sprinkled along the familiarity of the East Coast of America. Ireland both has what the U.S. lacks, and vice versa.

With this floating sensation comes a feeling of doubt. Being back in America, it was easy to remember what I left behind. I was on a straightforward path during my last year in New York. I worked a part-time job with a steady income and the possibility of growth. Alongside work I was in graduate school, earning the degree I needed to secure a permanent, full-time job afterwards, which came hand in hand with unfathomable luxuries like— drumroll please— health insurance!!! And paid time off!!! This sort of career stability and steadiness is something most of my peers have had since graduating from college, but something I have been very carefully working towards, recognizing that a career path in the art world is more circuitous. I always felt that the more permanent, dream job within my field would be my next step— maybe even the final step for the time being— after obtaining my MA.

But then, I was awarded a Fulbright. And I decided to spend another year in a short-term role, this time at the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin. Of course, this is by no means a shabby alternative to a job in New York. I am working in a museum on a curatorial project that I am extremely passionate about that is inspired by and contributing to long term goals. This too is a dream opportunity, it just isn’t a permanent one.

Aware of the lack of stability in my life as I floated back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean during the holidays, I couldn’t help but ask myself if I made the right decision. This summer I will be applying to jobs again, perhaps unemployed for a period as I search for the step that comes after the Fulbright. Will that next job be the one that sticks? When, exactly, will I reach the end goal? Do I even still know what that end goal looks like?

Last Saturday I stumbled into a bookstore and found myself drawn to the poetry section. Since my move to Ireland, my grandmother has made it very clear that she LOVES William Butler Yeats. She even declared that she loves W.B. Yeats more than Shakespeare. This is both shocking and brave for her to proclaim, given the fact that she holds a PhD in Shakespearian literature. Being the good granddaughter I am, I decided to make an effort to understand why this Yeats character is such a central player in my Nana’s life (is he extraordinarily handsome? Could this be the edge he has over Shakespeare??). I crouched down to the Y section of the poetry shelves, randomly selected a collective of Yeats poetry, and opened to the following poem:

What Then? His chosen comrades thought at school He must grow a famous man; He thought the same and lived by rule, All his twenties crammed with toil; 'What then?' sang Plato's ghost. 'What then?' Everything he wrote was read, After certain years he won Sufficient money for his need, Friends that have been friends indeed; 'What then?' sang Plato's ghost. ' What then?' All his happier dreams came true– A small old house, wife, daughter, son, Grounds where plum and cabbage grew, poets and Wits about him drew; 'What then.?' sang Plato's ghost. 'What then?' The work is done,' grown old he thought, 'According to my boyish plan; Let the fools rage, I swerved in naught, Something to perfection brought'; But louder sang that ghost, 'What then?'

Given my aforementioned feelings, it feels slightly eerie that I stumbled upon this exact poem. In it, Yeats presents a cautionary tale as old as time. The subject of the poem chases goals set for him by others, driven by the lofty promise of perfectionism. One accomplishment is never enough and cannot be belabored upon, yet by the time it seems that all has been accomplished—that life has finally reached that state of “perfection”— something remains amiss. External means of achievement and accomplishment ≠ fulfillment.

I opened my last blog post with a quote by Philip Guston, who is an artist I have known about for a long time but have never paid much attention to—despite his being an increasingly popular icon of the modern art world. Perhaps the reason for my lack of full-fledged interest in Guston is due to this popularity—the fact that other people are already saying things about him, so why bother scrounging around their scraps for any leftover morsels for me to say? Plus, I’ve seen the art he is known for: creepily cartoonish hooded figures, referencing KKK members, puffing on cigarettes and driving clown cars through barren landscapes. These paintings are unsettling to me. This is not a bad thing—good art often is unsettling. But I have not been keen to spend elongated periods of time studying these objects closely.

But then I was in London right before the holidays, and Guston’s retrospective was up at the Tate, and I thought: Okay, fine. YOU WIN, ART WORLD! Let’s see what all the fuss is about.

The exhibition blew me away. The thoughtfully curated show walked through the phases of Guston’s art making alongside explanations of the cultural and political forces that influenced his work. By the time I reached the final room, where those famous paintings I cited earlier were hung, I appreciated them because I understood how Guston got there. Guston’s journey, I realized, was not a straightforward one, but one that veered into unchartered territory, leaping between unique aesthetic experimentations teeming with frustrations regarding his own process and the state of the politically fraught world around him.

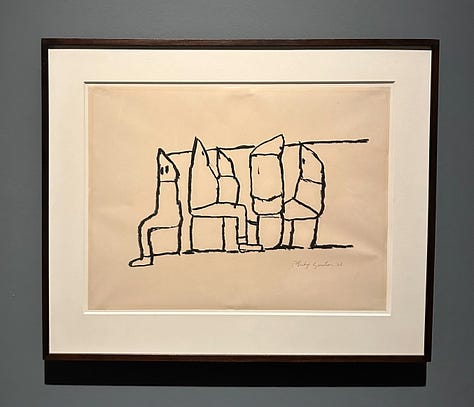

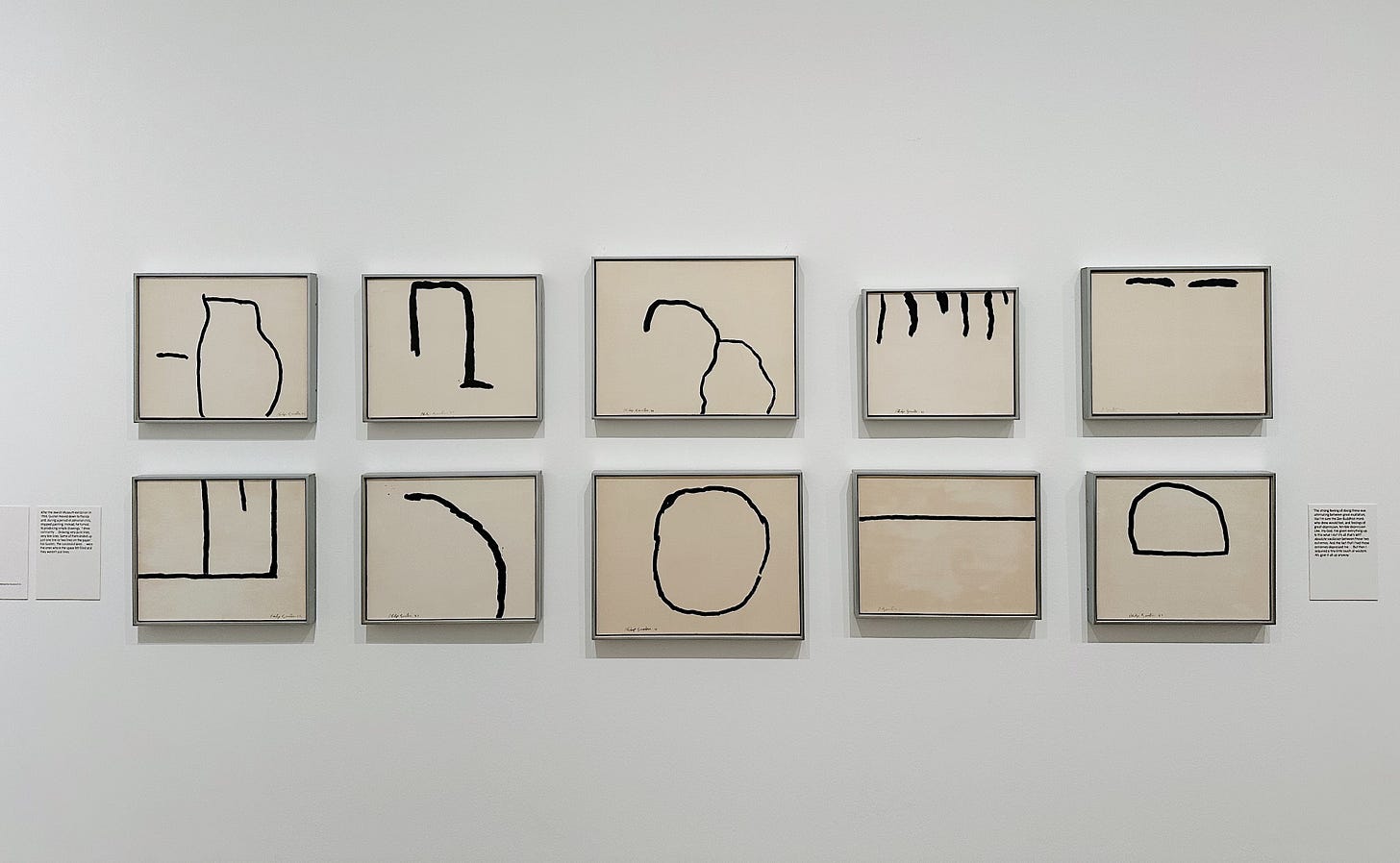

An unexpected group of objects especially stood out to me in the recounting of the artist’s artistic trajectory: 10 drawings of simple, black lines of ink, dragged in distinct shapes across white paper. These look nothing like the work for which Guston is known. Guston is celebrated for figuration, not abstraction; color, not monochrome; maximalism, not minimalism.

The drawings were created during a period of personal crisis for Guston around 1967, when he stopped painting altogether and turned to making simple drawings of, as he describes, “very pure lines, very fee lines.” Speaking about the “pure drawings,” Guston states: "I thought, what would happen if I eliminated everything except for the initial feeling, the paintbrush and ink...? It was as if I were putting myself to the test, to see what I am, and what I was able to do."

Eventually, the lines would morph into tangible objects. The outlines of hoods, of hands, of cigarettes would form upon paper as Guston built a key of characters that unlocked the figurative language his most monumental paintings are based on. In the artist’s personal battle between abstraction and figuration, figuration ultimately won.

But it is undeniable that period of abstraction was part of the journey. Later Guston would reflect on the years he created abstract art as a period during which he “hovered.” The artist declared, “I don’t want to hover. I want to nail it.”

I also want to nail it! But for now I am accepting the fact that hovering can be part of the journey. For hovering is what led Guston to the breakthroughs for which he is known. And the lack of hovering is what led to the subject of Yeat’s poem to reach the end of his life, still haunted by the ghost of Plato’s words: What then.

James and I took a trip to Clifden on the West Coast of Ireland two weekends ago. As recommended by every travel guide on the area, we drove our rental car along a panoramic route, aptly called “Sky Road.” What the travel guides do not mention is the fact that, at a certain point, Sky Road divides between two routes: “Lower Sky Road” and “Upper Sky Road.” Initially, we chose the lower path. We were blown away by the beauty of the sparkling still water that the road ran beside, in the shadow of the cliffs above.

Being the ever-curious duo we are, James and I couldn’t help but wonder what Upper Sky Road had to offer. So when we reached the end of Lower Sky Road, we decided to turn the car around and retrace our drive until we again reached the fork in the road, this time taking a sharp turn to drive along the upper route. Again, we were overwhelmed by the breath-taking views. This path snaked through the cliffs that loomed over us before. We now overlooked the bright blue salt water from above. We gained an equally stunning but brand new perspective on the landscape.

The beauty of floating—or hovering, whatever you want to call it— is that it does not tie me to a single path. Instead, like Guston, I can simply be guided by “the initial feeling, the paintbrush and ink.” For me, this initial feelings is a passion for art as a means of enabling new perspectives on overlooked histories. My paintbrush and ink are my Fulbright project.

What then? Plato’s ghost may ask me. The answer is simple: right now, I do not know. Perhaps the upper road or perhaps the lower road. Or maybe a little bit of both.

What a beautiful piece! So many complimentary elements that enhance the idea of journeying to greater awareness. And it’s all illustrated thoughtfully with beautiful photographs.

Thank you for conceiving this; reading it started my own day of seeking and creating on the right path—and the important reminder that I can always go back and try another path too!

Hi Allie, that’s beautiful. Guston’s minimalist drawings reminded me of Ellsworth Kelly’s “The Plant Lithographs” I saw at the Boston MFA last fall. Do you know if they ever crossed paths?…