On November 6th, with nowhere to turn, I turned to art.

I woke up at 4am that Wednesday with a sinking feeling in my gut. I rolled over and checked my phone to see that Trump won Pennsylvania. The reality slowly set in that America, once again, turned its back on women, on minorities, on marginalized communities, on LGBTQ+ people, on the climate, on the rest of the world. I felt crushed. But, mostly, I felt tired of being surprised.

The pounding dread, helplessness, frustration, and exhaustion I experienced in the early morning hours following election day came with an eerie yet identifiable sense of déjà vu.

On Wednesday November 9th, 2016, I experienced the same sense of shock. I woke up in my twin size bed in my freshman dorm at Dartmouth College. Consumed within my liberal bubble, I never thought that Trump would win. Devastated, I dragged myself to Psych1, where my professor spoke a few solemn words about the bleak state of our country, and then let us out of class early. I cried, I did my homework, I felt angry, I went to volleyball practice, I felt shocked, I ate dinner, I cried more, I got back into my small bed, I told myself that progress would come, I went to bed. Life, for me, went on.

I’d like to think I am not as naïve today. Over the last eight years, I have witnessed the divides that fracture our country, both personally and on a broader level. I have even left the United States and observed these divisions from afar. And yet, I still felt hopeful after casting my vote in 2024. I really, truly believed that more Americans would vote to see a woman in office— a minority in office. I thought that, even if people did not think she was the best candidate, they would choose her over a rapist. That women would choose her over a rapist. I was wrong.

Still processing, I took myself to the Whitney Museum of American Art.

I wasn’t looking for anything in particular. I felt, however, that art may offer what it has offered me and countless others in the past: a form of therapy, mourning, reckoning, escape, evidence, and reflection.

Within the Whitney’s sleek structure in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, I chose to revisit the museum’s permanent collection. Comprised of objects from a diverse range of artists, the Whitney’s collection pushes boundaries both metaphorically and physically, challenging a singular definition of American art.

I immediately found myself drawn to a canvas that I have observed many times before, and even written about in graduate school: a 1961 Edward Hopper painting titled A Woman in the Sun. The work depicts Hopper’s wife, Josephine Nevison Hopper. Jo, as she was known, was an artist in her own right. Yet, as it goes, the talented artist largely dedicated her time and efforts to the success of her acclaimed husband, who notably treated her— his repeated muse— like garbage. When Hopper painted this particular work, Jo was actually seventy-eight. The painting is clearly shaped by his imagination and imbued with voyeurism.

On this particular day, I saw A Woman in the Sun in a new light. I looked at a woman stranding erect and confident, yet simultaneously vulnerable and imbued with grief. I noticed a sadness in Jo’s eyes that I previously overlooked. I realized the objectification of Jo’s body at the hands of her husband. I understood Jo’s continued objectification, today, as her naked, idealized body hangs on the walls of the Whitney Museum, rather than her own art.

Continuing onwards, I passed by Norman Lewis’s American Totem from 1960. Amidst the development of Abstract Expressionism, Lewis— one of the few black artists associated with the movement— maintained subtle figuration within his gesture. The ghostly form of a Klansman denies any escape from reality within the beauty of abstraction.

Around the corner, nine, large-scale canvases collectively tell the story of what appears to be an act of torture, but, actually, illustrate the artist’s illegal abortion in 1967. Juanita McNeely’s painting Is It Real? Yes it is! conveys the pain and confusion of a story that was, at the time, dangerous to tell, yet commonplace. How much, or how little, has changed? I wondered.

On the next floor, I encountered an installation of chopped tree trunks across the gallery by Maya Lin. Nearby, I was entranced by a glimmering fire, created out of fragments of glazed ceramic, pieced together. By Teresita Fernandez, this work is titled Fire America.

One floor down, and I came across Catherine Opie’s 1993 photograph Self-Portrait/ Cutting. The Hood Museum at Dartmouth holds a version of this photograph that, as a college student, I felt squeamish looking at, and therefore avoided. On this day, I forced myself to stop and look, closely. I stared at the artist’s crimson blood, dripping out of cuts within her back that render a stick-figure couple in front of a quintessential home. Within her own flesh, Opie painfully questions the desires and realities of domesticity in relation to Queer culture.

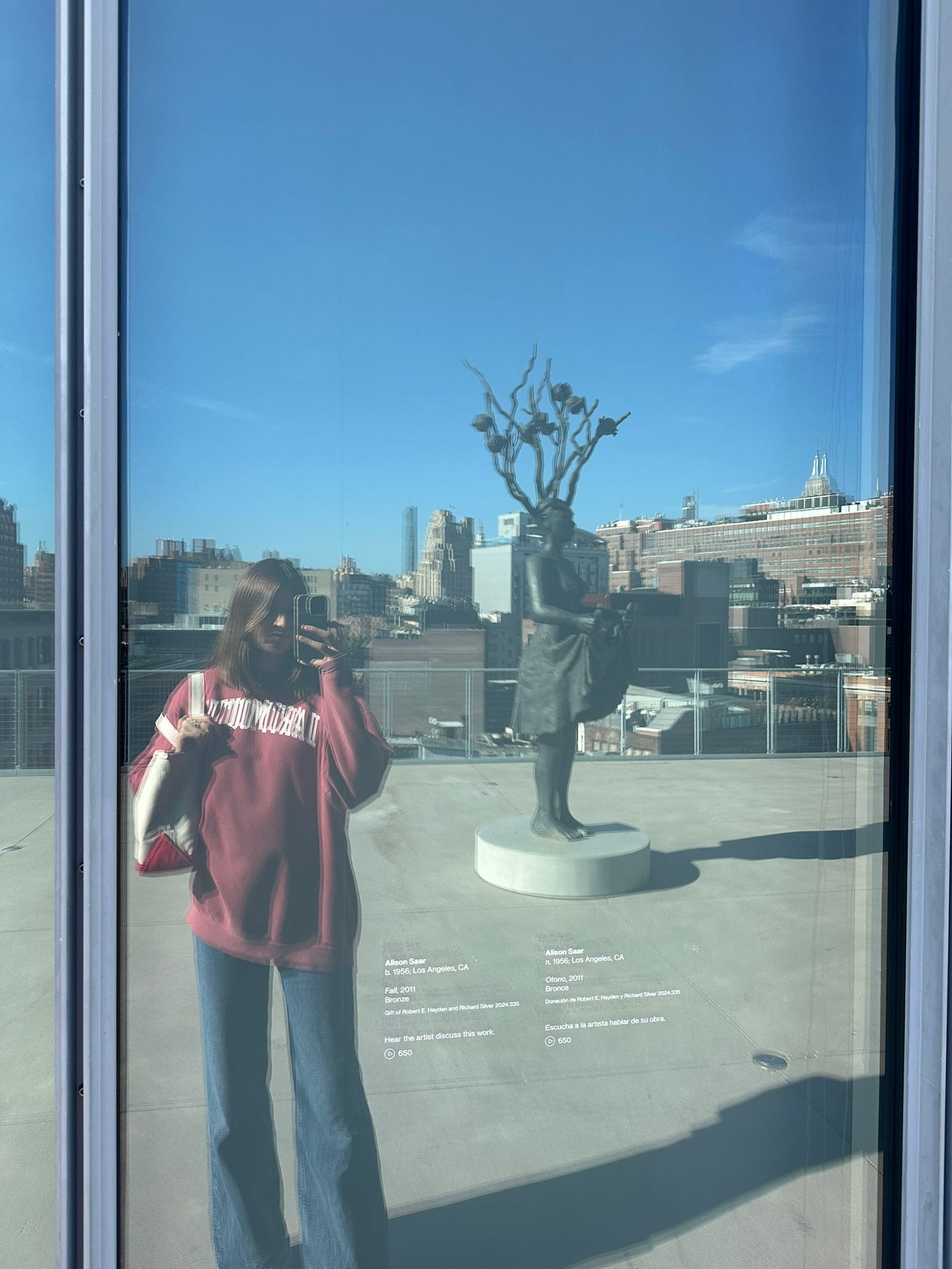

On the Whitney’s terrace, I found Alison Saar’s bronze sculpture of a woman silhouetted against the skyline of Manhattan. The subject’s tall hair morphs into a blooming tree, the bounty of which she offers outwards.

Leaving the museum and walking up the High Line into Chelsea, Glenn Ligon’s billboard shouts at pedestrians AMERICA, with each letter crossed out besides the M and E.

Wandering into Hauser & Wirth, I observed Lorna Simpson’s contemporary approach to abstraction: large-scale canvases, loosely brushed with metallic paint, featuring small black dots across the surface. Bullet holes.

Upstairs, I found portraits by Annie Leibovitz, idiosyncratically pinned within a grid of blank spaces. This experimental “stream of consciousness” (as titled by the exhibition) seems to suggest the acclaimed photographer’s process of experimentation within her studio. The unassuming, 4x6 images feature Michelle Obama, Joe Biden, Maya Angelou, Elon Musk, Kamala Harris, Serena Williams, and countless other influential figures. Among them, many spaces are left blank.

I began writing this post two weeks ago. I keep sitting down to wrap it up, and send it out. But I find myself struggling to tie it all together.

As more time passes, the more I disassociate from that feeling of dread and anger and exhaustion that drove me to look at art on November 6th. Just as it did in 2016, the initial shock wears off and life seems to carry on— especially the life of me, a white, cisgender young woman living in New York City.

However, visions of the artworks I encountered on November 6th continue to echo in my mind’s eye. Their stories are, of course, extremely relevant in this moment we find ourselves in: these are stories of womanhood, of racial violence, of our endangered environment, of politics, of abortion, of queerness, of violence.

But most of these artworks were created long before November 6th, 2024. In fact, many of them were completed before the advent of the 21st century. Thus, the objects’ feelings, themes, and concerns are not new. Rather, they are a realities that history has already encountered.

In response to this, some may say that history repeats itself. But I say: histories live on. Without real resolution, histories are all at once normalized and compounded. The angers, frustrations, and divides surrounding the unresolved intricacies of past events or movements remain relevant. And then we find ourselves years later, shaking our heads, wondering how we can all at once have come so far while still remaining so far behind. And then we go to bed. And then the shock wears off. And then life moves on.

Art does not move on. Instead, it asserts its perspective into the context it reflects, claiming space while proclaiming: this is real. The physical artwork then lives on, preserved within our cultural institutions and presented to wider publics, offering evidence that announces: this was real. Art provides archives that help us remember and learn; relics that ensure we do not forget the enduring complexities of contemporary moral issues that continue to penetrate society, leaving divides within their wakes.

Art asks us to reflect. To acknowledge. To recall the past. To complicate the past. To see the past in new lights. To see the present in new lights. To find ourselves, our situation, and the situations of others— of our country—in the output of our visionaries, past and present, so that we do not— we cannot— simply move on.

Instead, art urges us to stand still. To look at what once was. And, in this process, to grow, to blossom new ideas out of ourselves, to harvest the bounty of these ideas, and to offer them outwards. To then begin the work of filling in the blank spaces that remain on the wall of the studio.

Amazing post, Allison. Here's to NOT moving on in the wake or our national political calamity and the power of art to help up process and energize ourselves going forward.