Lately I feel like my brain has been working in overdrive. I sat down numerous times over the past few months to write a blog post, but with major deadlines looming over me, my energy (and rapidly dwindling brain power) continues to be pulled elsewhere. Forgive me if this is a particularly long piece of writing, but I have much to say after my months of silence.

I came to Ireland to curate an innovative exhibition based on community participation; to engage a small group of youth with the Hugh Lane Gallery’s collection and curatorial practice, and then to work with them in ideating and executing a show. The resulting exhibition, Time & Time Again, opens on 9 July—a date that is rapidly approaching.

When I first sat down with my young visionaries to brainstorm an idea for the exhibition, I was sure it would be an agonizing decision. Narrowing down one idea amidst eleven diverse visionaries and over 2000 artworks in the collection?! That felt like a near impossible task. However, I was (pleasantly) surprised when the group swiftly and unanimously agreed on a theme they wanted to address: the future. The future, they explained, is a notion that consistently occupies their thoughts. It is all at once a dreamland of opportunity, where goals can be accomplished, as well as a place of ambiguity and uncertainty.

This contradictory outlook on the future– from excitement to anticipation to dread– is not something the group of sixteen-year-olds had to explain to me. These feelings are something I can very much relate to (for further information, please read literally any of my prior blog posts). In fact, I believe many individuals, across time and place, can empathize with the contradictory emotions surrounding the future.

This universally conflicting outlook on what’s to come has much to do with the fleeting and overlapping quality of time, which results in a collective inability to live in the present moment. As one of my students aptly stated: “I am at the present, which was once my own future.” Today quickly becomes yesterday as tomorrow becomes now. Histories shape our present moment, which dictates what is soon to come.

With all of this in mind, the young visionaries and I realized that our exhibition could not consider the future in isolation. Rather, we had to expand our show to encompass the entangled temporalities of the past and the present in order to make space for conversations about what lies ahead of us—on an individual and communal scale.

Thus, Time & Time Again utilizes the Hugh Lane Gallery’s collection to addresses the passage of time as it relates to our future: the individual and collective narratives that shape the present moment, history’s tendency to repeat itself, and the uncertainties surrounding what’s to come. How can we live in the moment, while acknowledging the past events that shape the here and now, and also working to build more inclusive futures? Through a space for reflection and dialogue on the complexities of time, and time again, our exhibition strives to address this question.

Ironically, amidst bringing the exhibition to life, I find myself absorbed in the stressors of fleeting time and ambiguous futures. I lose focus on the present moment as I spend my days working with designers, printers, painters, art handlers, conservators, artist estates, and so on. As I switch abruptly from organizing loan paperwork, to editing wall text, to trying to hire a contractor to build a floating gallery wall (I apologize to all of those who have had to listen to me agonize over how I will “BUILD THE WALL!” over the past few months), all in time for that looming date of July 9th, I completely disassociate from the present moment.

It goes without saying that my solo trip to Venice a few weekends ago came at a good time. A great way to forget about your problems? Jump on a flight to Venice and, upon touchdown, head straight to a wine bar ideally tucked beside the glistening canals, where you only have to spend a mere eight euro for a perfectly ratio-ed Aperol spritz and cicchetti meal deal, which you can then enjoy as you peacefully read your page-turning novel amidst soft Italian chatter. (I am going to choose to leave out the part where the seagull snatched the delectable looking truffle-prosciutto cicchetti out of my hand as I went in to take the first bite, slapping me across the face HARD with its wing in the process, and flying away leaving me and the MANY onlookers around me stunned).

Anyway, I did not just go to Venice to drink Aperol and eat good food (and be assaulted by seagulls) in the company of strangers. I went to Venice for the 60th international Art Biennale. Yeah yeah, only I would destress from my career in the arts by spending time looking at more art.

You may recall my talking about the Venice Biennale in one of my earliest blog posts (she says as though she has a faithful alliance of fans gripping onto every word she publishes). For those who need a recap: the Art Biennale in Venice is the world’s largest art exhibition. The official show represents hundreds of international artists under a collective theme. Alongside this, individual countries select a representative artist whose work is exhibited in separate displays. A handful of countries have their own permanent pavilions, transformed every two years by artists’ topical visions. As if that was not enough art, further collateral events pop up around the city’s museums, churches, and palazzos, saturating the old city with new art and ideas. This biannual event is truly the Olympics of the art world.

Two years ago, my solo trip to the Biennale was a life altering adventure. Alone in Venice, connected with strangers by the incredible ideas conveyed by the expansive breadth of art, I decided I wanted to move abroad and continue to explore art’s connective capacities across borders. When I got home, I discovered the Hugh Lane Curatorial Fulbright and began crafting an application to curate an exhibition with Irish youth, exploring art as a means of connection– something I felt so strongly in Venice. And here I am, two years later, doing exactly what I said I wanted to do.

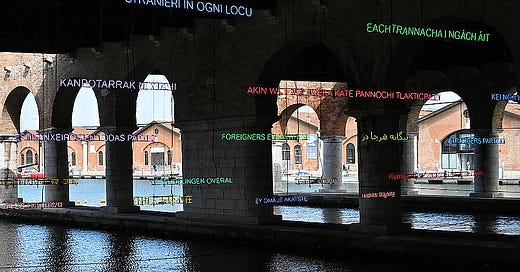

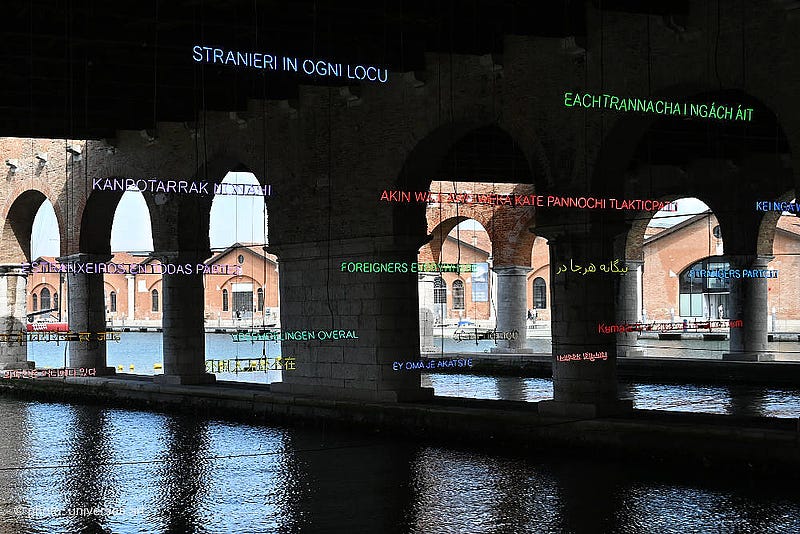

This year, the Venice Biennale is curated by Andriano Pedrosa, the first South American curator of the famed exhibition, under the title and corresponding theme “Foreigners Everywhere.” In Pedrosa’s own words: “wherever you are, you will always encounter foreigners—they/we are everywhere.” He further suggests that “no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner.”

Foreigners Everywhere! The title is all at once a cry of excitement, a chant of despair, and a call to action. The artwork throughout the Biennale reflects all of these interpretations, among others, by grappling with what it means to be the foreign, the distant, the outsider, the Queer, the indigenous, and so on.

Much of the displayed artwork considers the influx of displaced people across Europe and the Mediterranean. For instance, French Moroccan artist Bouchra Khalili’s installation of multiple films, collectively titled The Mapping Journey Project, screens the hands of migrants, who mark maps as they narrate their complex tales of migration and movement. I was transfixed and emotional by the stories these anonymous subjects told as they traced lines around distinct countries, recording their quest for stability.

Other works within the exhibition explore the identities of marginalized groups within specific communities. Nigerian born artist Karimah Ashadu’s film Machine Boys, for example, documents the consequences of banning motorcycle taxis, known as okada, in Lagos. Her thoughtful recordings intimately illuminate the machismo collective of these motorcycle drivers, now legally jobless, yet continuing their services in order to provide familial and personal stability—and perhaps maintain a sense of identity.

South African artist Gabrielle Goliath also recorded the testimonies of marginalized identities—this time considering the normalization of patriarchal and colonial acts of violence and trauma. Yet in Goliath’s immersive, sonic installation, Personal Accounts, the artist chose to rid the recordings of actual words. Instead, the paralinguistic elements of the subject’s stories are projected at jarring volumes: the breaths, swallows, and sighs that seem to convey more than words could ever communicate.

A lot of artists in the Biennale considers the aftermath of colonialism across people and places. Pablo Delano forces audiences to confront and contemplate the colonial exploitation of Puerto Rico in his installation The Museum of the Old Colony, which gathers archives documenting how Puerto Rico was established and advertised across America.

Andriano Pedrosa was clearly keen to include foreigners to the history of art as well; those typically swept into the shadows of the discipline to make room for the (usually white and male) titans of art history. A huge, salon-style hang in the central exhibition includes portraits by largely unrecognized artists in the narrative of modernism. The severe, 1941 self portrait of Buenos Aires artist Raquel Forner, expressing her trauma from the Spanish Civil War through a sorrowful yet resilient gaze, stood out to me.

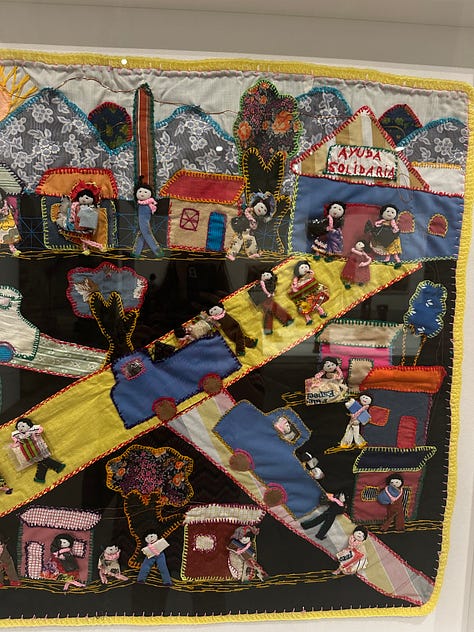

The artwork of Arpilleristas, or unidentified, rarely acknowledged Chilean artists, is also prominently on display. The group takes its name from the Spanish term for burlap sacks, which serve as the backing for the artists’ embroidered renderings of Chile during Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship, reminding viewers of the continuous struggles for change in the South American nation.

Some artwork looks at places instead of people in considering the theme of foreigners. Kiluanji Kia Henda’s photographs beautifully document the painted protective metal railings found in buildings and houses in Angola. These architectural features are especially prevalent, I learned, in big cities in the Global South, where significant disparities exist amidst populations. Colombian born artist Daniel Otero Terres considers architecture too, offering a colossal installation: a stilted structure made from locally collected materials, with water flowing through it. The object reflects the ecological crises inherent to the lives of marginalized Colombians by evoking the unusual system of stilt architecture designed to collect rainwater and provide inhabitants with unpolluted waters. This issue is blatantly paradoxical: in the heaviest rainfall region, communities face severe challenges in obtaining clean water.

In the different country’s pavilions, artists continue to grapple with this idea of Foreigners Everywhere. In Austria’s somewhat imposing space, USSR born artist Anna Jermolaewa reflects on the use of ballet as a means of censorship and distraction. During points of political turmoil in her home country, Swan Lake was played on repeat on the televisions. Through actual live ballet performances within the pavilion, Jermolaewa transforms the peaceful, melodic dance into a form of political protest, calling for a regime change in Russia.

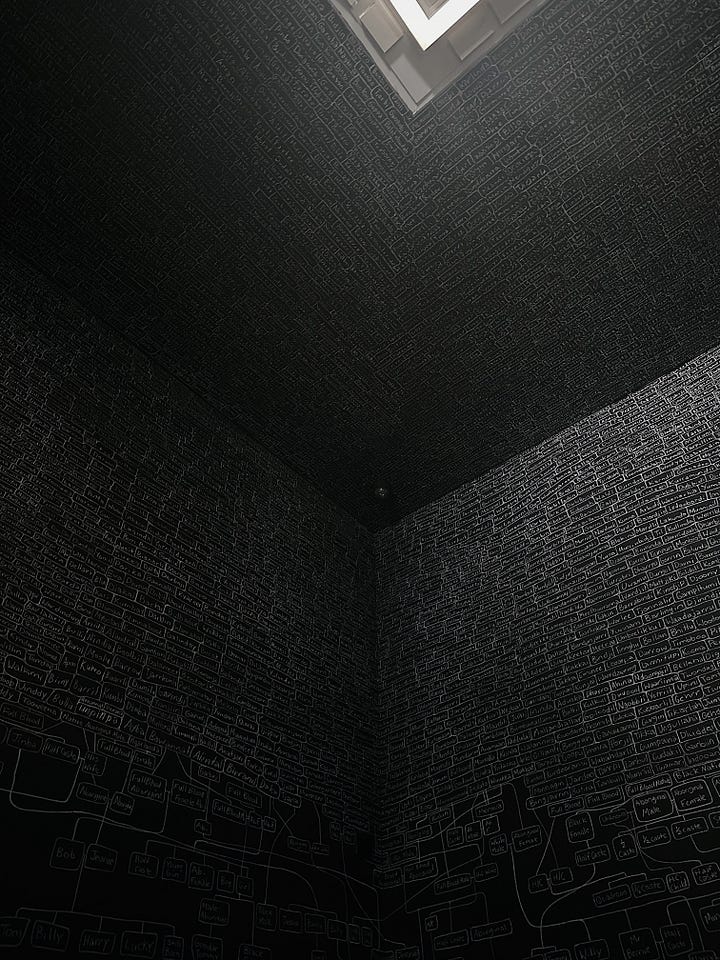

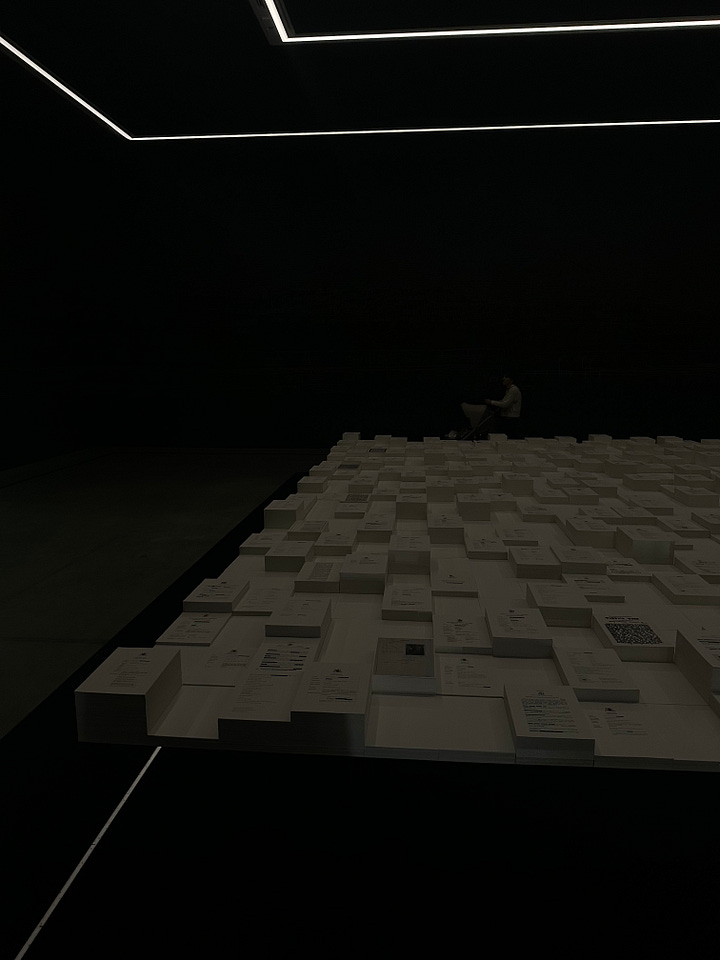

A large surface overtakes the center of Australia’s pavilion, unreachable due to an encompassing moat of shallow water. This tabletop is covered with stacks of redacted documents recording the deaths of Indigenous Australians in police custody. The walls of the darkened space are covered with an incredibly intricate family tree—hand drawn by the artist, Archie Moore. This chronology of people extends over 2,400 generations and attempts to record the heritage of indigenous populations. The message is clear: we are all related.

The Netherlands notably chose an artist collective of Congolese plantation workers, based in the heart of the Democratic Republic of the Congo on land formerly owned by a British-Dutch cooperation, to represent their country. America, too, turns to the perspective of the colonized through the art of Jeffrey Gibson, whose vibrant, geometric, often textile-based artwork engages with America’s complex relationship to indigenous and Queer populations, mandating these identities as central to the American experience.

I’ve been back Ireland– my home away from home– for a few weeks now. Since the Biennale, I have been thinking a lot about what it means to be a foreigner.

In many ways, I am a foreigner here in this city. I am American– and I am not Irish American. No family brings me to Dublin, no lineage connects me to this place. My foreigner status in Ireland became especially clear to me when I returned to New York around the holidays and became hyper-aware of the immediate comfort I experienced. I realized that, every time I open my mouth to speak in Dublin, my position as an outside becomes obvious to me and those around me. In Ireland, I am constantly self-conscious of how my mannerisms, traditions, and slang out me as a foreigner. Of course, I am hardly experiencing any sort of culture shock in Ireland. But nonetheless, I am not from here— and I am reminded of that every day.

With this said, I do not feel any negative impacts of being a foreigner. In fact, I have felt nothing short of welcomed by Ireland and its people. I easily found a comfortable home, even amidst a housing crisis. I made incredible friends, even without knowing anyone upon moving. I have been offered a platform for my voice and my passions, even with no prior connection to Dublin. The Hugh Lane Gallery and the Fulbright Committee have actually glorified my being a foreigner by affording me the opportunity to introduce new perspectives in Ireland through cross-cultural exchange.

Here in Dublin, migrants– especially those from Ukraine– flood into the country, seeking asylum. Encampments have appeared across the city, noticeably increasing since my move. Alongside this, an outcry against these people and their presence has become more and more vocalized. I have witnessed anti-immigration, nationalist protests where the chants “go home!” or “Irish lives matter!” are eerily reminiscent of similar words echoed across my own country.

The challenges often inherent to being a foreigner– those explored by many artists in the Venice Biennale and those I witness by the marginalized populations in Dublin—are not something I can relate to. I do not live in fear of what tomorrow may hold. I am not told to return home. I have a home to return to; a place on this earth where I do not face the status of being foreign.

Much of the art being displayed in Time & Time Again introduces recent histories as a means of considering what is to come, serving as a reminder, or perhaps warning, of history’s repetitive tendency. My favorite work within this vein is a sculpture of a couch, aptly titled Sofa, by Belfast-born artist Rita Duffy. Sofa has an unsettling effect on the viewer. A piece of furniture that is usually commonplace and comfortable is transformed into a sharp and delicate object through the use of thousands of hairpins, camouflaged as lush fabric upon the sofa’s surface. In the context of Duffy’s biography, Sofa may represent the artist’s early life during the Troubles in Northern Ireland; how her home of Belfast, a city that was once so common, comfortable, and reliable, became so dangerous and uncertain. The city became foreign. Or, perhaps, Duffy was cast as the foreigner.

What a privilege it is, for me, to have a comfortable sofa to rest on, both in Ireland, and in America, and likely elsewhere. What a privilege to be able to analyze art that relates to this concept of “foreigners,” but to do so as a third-party observer.

One of the things I love about writing is tying together multiple strands of ideas and anecdotes in a succinct conclusion that (I hope) leaves my readers feeling satisfied. Sometimes I find that I actually write backwards, starting with an idea for an ending and then working my way to an introduction.

But right now, as I try to wrap up this piece, I am at a lost for a singular takeaway uncovered from my musings the state of being foreign, or perhaps being not so foreign.

The only thing that immediately comes to mind is a quote by James Baldwin. This is a quote that, many years ago, inspired my drive to be an art historian who approaches art as a tool of understanding new perspectives on histories, humanity, and the present moment:

An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to help you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are.

-James BaldwinWhen words fail me, or when I lack a conclusion, I continue to return to art. To reflect on the doom and glory conveyed through films of migrants’ hands, victims’ swallows, the stories of okada, the piercing gaze of Raquel Forner, the visceral command of Rita Duffy’s sofa. To utilize these artistic testimonies to reflect on the doom and glory of who I am and what I am; my state of being not so foreign in a somewhat foreign place. To continue providing spaces where others can accessibly and safely vocalize their perspectives on these complex themes and open-endings as we collectively anticipate what the daunting future may hold.

This has truly made me stop and think, about our world, about the state of young people, about my good fortune, and about what an exceptionally talented writer you have become. You express compassion, vulnerability, insight, and wisdom all pivoting around your lifelong love of art.

Thank you for writing and sharing this.