After the longest month ever (January), life has picked up speed. This has to do with a few things:

My work is busier than ever. The curatorial project that brought me to Dublin is moving full speed ahead, I am giving a handful of lectures, and— in order to prepare for both of these things—I am meeting with local artists and curators across Dublin.

I now own an immersion blender, the possibilities of which are limitless. Therefore, my attention is needed in the kitchen.

A freeloader has moved in with me for a few weeks (aka James, who is on a mandatory paid leave between jobs— must be nice).

I actually feel like I have friends now.

I am finally comfortable with driving on the left side of the road (hence, more adventures).

I realized that every European country I have ever dreamed of visiting is a short and cheap flight away; as such, weekends are now filled with travel.

The sum of these elements (among others) has led to February flying by— and led to my being a pretty bad blog writer. Sorry that I am now a popular gal with an immersion blender.

With a moment to finally breathe, I am taking the time to reflect on the past few months, and how abruptly the pace of my life has changed. During the glacial month of January, the days were short, dark, and rainy. I got home from work at 5:30 pm, and it was already pitch-black outside. Without much more to do I made an outrageously early dinner (this was pre-immersion blender, so this wasn’t a very exciting occurrence), and then I went to bed at an outrageously early time. I woke up early and went to the gym. Then I went to work. Then I did it all over again. I was also abiding by dry January (okay, fine, damp), which led to an unusually quiet social life. Then again, most of my new friends were either still on holiday or also residing in an equally mundane state of being.

And then, all of the sudden, things took a sharp turn. Now I feel like I am sprinting towards the finish line of my time in Ireland—which I know is crazy, because I have a whopping six-ish months left. But it feels as though each weekend is booked with visits from friends, family, or travel, while each week is overflowing with work. After days that felt long and empty, I now feel as though there is not enough time to do all I want to do.

Last week at my work place, the Hugh Lane Gallery, I gave a public talk about Slow Looking. Truthfully, I largely chose this topic out of necessity: I only had a week to prepare and I had given a presentation on Slow Looking in the past. But as I recycled my pre-made PowerPoint slides, sprucing them up for an Irish audience, it became clear how relevant the topic of Slow Looking is to my life right now.

First, a little context. What is Slow Looking, you may ask? I am SO glad you inquired. Slow Looking is defined by its title. It is a practice of engaging with art based on the idea that to understand an object simply requires elongated observation. The amount of time spent observing the given work of art can vary: maybe ten minutes, thirty minutes… maybe, for the brave, an hour. Recent studies have shown that museum-goers spend, on average, twenty-seven seconds with a work of art. So, to be honest, if you are spending even five minutes with an artwork you are technically well within the realm of Slow Looking.

The Tate explains that, “slow looking is not about curators, historians, or even artists telling you how you should look at art. It is about you and the artwork, allowing yourself time to make your own discoveries and form a more personal connection with it.” Despite my being an art historian, I love this idea of rejecting conventional research—of breaking away from the confines of academia and scholarly jargon that has traditionally scared audiences away from seemingly elitist galleries or museums. I mean, be honest: how often do you find yourself rushing to read the object label next to the artwork, seeking instruction on what you should be looking for in the canvas in front of you, rather than reaching your own conclusions? Rather than just looking, and feeling?

Slow Looking promises to make art and art’s meanings more accessible. You don’t need a degree or complex knowledge. You don’t even need an understanding of the artist’s intentions. You simply need time (and maybe a bench). And then you rely on what you see and what you feel. To me, that’s what art should be all about.

One of the main things I have come to realize about Slow Looking is that every individual’s takeaway from observing the same work of art for an extended period of time will differ—sometimes dramatically.

This goes against the traditional art history 101 course, when the professor rushes through slides of iconic works of art listing an artist, title, and year, and then quips an easy-to-remember, digestible meaning: “WARHOL’S SOUP CANS: CONSUMERISM IN AMERICA. PICASSO’S LES DEMOISELLES D'AVIGNON: A REJECTION OF PICTORIAL CONVENTIONS IN THE ADVENT OF CUBISM AND PRIMITIVISM.” Distilling art to these one lined takeaways is diminishing. It turns art into something that has a single, right answer; scares away audiences who feel as though they may not have the conventional knowledge necessary; and leads to museum goers running to read that pesky object label, or avoiding museums altogether.

To me, there is beauty in everyone having distinct, even diverging experiences when confronted with art. In fact, I believe that this encapsulates the beauty of art all together. Art can be all at once a universal phenomenon, while simultaneously accounting for individual experiences. Art can provide a space for dialogue: for agreement, for disagreement, for debate. Through the action of seeing and discussing what we see, art can allow us to become more open minded— more susceptible to new views and interpretations and previously unseen takeaways and perspectives.

A few weeks ago I traveled to Paris. The trip was perfect (besides a slight snafu at the end when I ended up at the airport with two passports, my travel partner Jemma’s AND my own, while Jemma found herself passport-less at the train station. But we’ll ignore that for now).

The trip was perfect. Jemma and I leaned into our tourist personas by waking up bright and early— long before the typical 11am rising time of the locals, who seemed disgruntled by our eagerness. This in no way bothered us; as the first in line at the local boulangeries, we had the space to thoughtfully choose the best-looking fresh croissant from the case, which we then clenched in a butter-stained brown paper bag as we walked down the Seine, searching for the best vista to enjoy our treasure. We then got a head start as we took full advantage of the ongoing sales, stopping only for a light lunch of mussels, steak, wine, and chocolate mousse at a bustling bistro. In the afternoons, we recounted our days to our soft-spoken Air BnB host Morgan, who offered us a selection of his homemade jams with a fresh baguette every morning (we obviously did not turn down this generous benefaction and therefore, yes, we did have two breakfasts each day. An appetizer (bread) and a main course (more bread), if you will). During the evenings, we stumbled into jazz bars after candlelit dinners. We shyly befriended our French waiters, embarrassed by our lack of the local language, but proving our worth by boldly ordering things like sea snails and veal head (partially due to menu items becoming lost in translation).

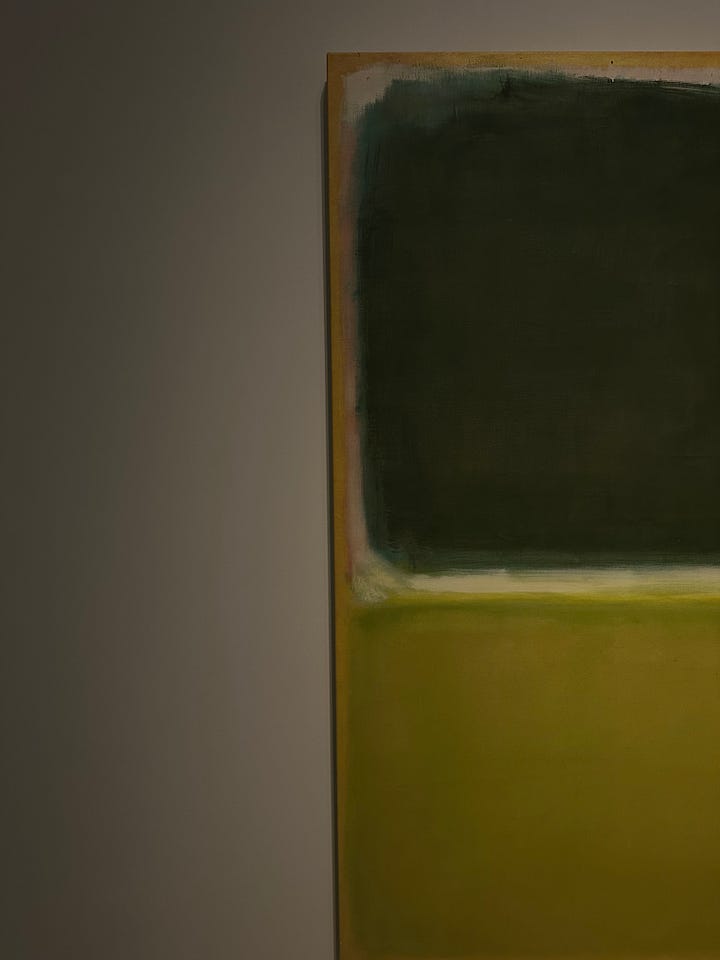

And then, finally, we went to see art. Particularly, we ventured to the Louis Vuitton Foundation to see the acclaimed Rothko exhibition—a show that largely inspired my trip to Paris. Even though I knew the retrospective was meant to be good, I had my hesitations. Here was another artist who I only had really experienced via those one liners lectured at me early in my art history education: “ROTHKO: ABSTRACT FIELDS OF COLORS.” But my experience in Paris would change all of that.

The exhibition began with a large Rothko quote, boldly mounted on the wall: My art is not abstract, it lives and breathes. After reading this line, along with a short introduction, the crowd of bustling museum-goers, along the skeptical critic (me), were funneled into dimly lit galleries, meant to emphasize Rothko’s vibrant use of color in his delicate applications of paint,

While I did not spend a full hour or even thirty minutes with a given work of art in the show (poor Jemma would have strangled me), I did take the time to look, slowly, at the collective objects. To not rush from one to the next or focus only on the labels, but to instead observe the canvas’s edges, which gave insight into Rothko’s incredibly meticulous layering of thin sheets of paint that achieved the luminous canvases for which he is known. To admire the colors the artist chose, and how they varied throughout his career. To seek feeling and experience within the realm of abstraction.

The objects did, indeed, live and breathe. Although I gazed upon seemingly simple, blocks of colors, the overall effect stimulated emotions and memories within me. In a green-toned canvas I found childhood memories of me and my sister, skipping through the state park in our hometown, running up rock faces alongside the park’s lake as our dog splashed in the water alongside us. The work hummed along the edges, eliciting a warm feeling that felt nostalgic— reminiscent of the sun buzzing on those warm summer afternoons. In another canvas, comprised of warm fields reds, oranges, and yellows encompassed by a meticulous blue perimeter, which bled out from the background, I was brought to my final sunset in New York City. There I was, sitting on a picnic blanket with all my closest friends the evening before I moved to Dublin, my thoughts slightly muddled from the warm white wine in my plastic cup. In that painting I saw the moment as the dark blue evening began to consume the last rays of the sun, which dipped into the Hudson River in front of us. I felt that bittersweet moment when my chapter in New York temporarily closed in anticipation of a new adventure.

And then I reached a room of more unusual Rothko paintings, less bright and multi-colored, instead rendered through a darker palette. These objects were Rothko’s Seagram Murals, originally commissioned in 1958 for the Four Seasons restaurant in New York City’s Seagram building. The objects were meant to provide an immersive experience for visitors. In the exhibition, I found myself entranced by a mural decorated with deep red shapes upon a crimson-colored background. The difference between the two paints is so subtle that only a slow looker may even notice the fact that the canvas withholds two tones. The patches of red hardly bleed through the muted backgrounds, leading to their being “darkly luminous,” as a critic so aptly noticed.

This painting also breathed, although more softly, more subtly. As I slowly looked, it breathed out memories of January: a quiet month, a dark month, a monotone month, a slow month, a month I didn’t really care for. But the longer I looked at this painting, discovering the hidden beauty concealed within the initially unassuming canvas, the more appreciation I had for it. The memories of January that the object elicited began to take on a new sort of virtue. January: A month to pause. A month to find a routine. A month to be comfortable being alone. A month to find purpose in a new country. A month to reflect on being in a new country, espeically after having been reminded of life at home over the holidays. A month to recover from the holidays. A month to be quiet. A month to move slowly, to think slowly, to look slowly.

I have found that there is always one ubiquitous takeaway from Slow Looking, no matter what object is being observed: there is always more than immediately meets the eye. This is true when we slowly look at an object like a Rothko painting; simple in concept but easily complicated. This is also true when we slowly look at our lives; simple in concept but easily complicated.

Just as we slowly observe art, we too can slowly observe our surroundings, our peers, our communities, ourselves. We can learn to carefully and intentionally and slowly take time to look for new perspectives and purpose within the contexts and narratives that surround all of us. Instead of belaboring upon a grim month of short days and dark skies, for example, we can embrace this time as an unorthodox pause amidst the business of life, during which we can breathe and observe what may otherwise go overlooked.

When we do this, when we practice Slow Looking in the quiet moments of our day to day lives, we perhaps will also become more perceptive to the small moments during the rushed hours. Not just the exciting weekend plans and the overwhelming to-do list at work. Not just the clock ticking on an experience, and the quickly fleeting possibilities that experience may hold. But, also, the cloudless blue skies emerging in the wake of winter months. The crisp smells of the start of spring filling our lungs. The livings and breathings of our every days.

stunning beautiful and perfect, as per usual

I love Allie x immersion blender