A few posts ago I briefly mentioned that I turned to art as a means of therapy. It was a beautiful Sunday in Dublin about three weekends ago. The sun was shining and felt warm on my skin, despite it being a chilly temperature outside. The green grass looked even greener than usual. And yet, despite the immense beauty that surrounded me— and despite having spent a weekend with new friends at the tail end of a fulfilling week of work— I felt melancholy and uncertain.

Something I have acutely experienced since my move to Ireland is the transition between high highs and low lows. These highs and lows often occur in close succession, or even become intertwined. In novels and movies, or on our social media feeds, we don’t usually bear witness to these in-between moments— the times that lack a clear feeling of good or bad and instead consist of nuanced emotions. These are the moments that fall outside of the binaries we typically employ as a means of attempting to categorize our life and our feelings.

This dismissed in-between space is where I found myself on that particular Sunday: outside of the binary, a little lost, a lot alone. Objectively, in that moment, life was all I ever hoped for. I was in a new country with no plans, beautiful weather, and endless paths for exploration. I had just finished brunch with a group of new friends, who are working towards their Masters at Trinity. But after they left the café to take themselves to the library, I found myself alone and unsettled, wondering: “Now what?”— both in terms of that precise moment and the bigger picture.

And so, at a bit of a loss, I did what I do best: I went to a museum.

I had no idea what exhibition was up or what to expect on this unplanned trek out of the city center to the Irish Museum of Modern Art— a museum I had not yet visited. When I arrived, I was pleasantly surprised to stumble upon the final week of a large scale exhibition highlighting the work of American artist Howardena Pindell. Although I recognized some of Pindell’s work, I did not know much at all about the 80 year old artist, curator, and educator. I quickly learned that Pindell builds colorful and textured compositions through laborious processes including hole-punching, layering, drawing, cutting, stitching, and spraying. Although Pindell was trained as a figurative artist, she has spent much of her career— the majority even— experimenting with abstraction. As a Black, female artist, Pindell speaks about the external pressure she felt to use her art as a means of translating her experience as a minority in the 60s and 70s. Even her abstract work was often read through the interpretive lens of her “race.” Yet, as Pindell explains, “I am an artist. I am not part of a so-called "minority," "new" or "emerging" or "a new audience." These are all terms used to demean, limit, and make people of color appear to be powerless. We must evolve a new language which empowers us and does not cause us to participate in our own disenfranchisement.”

I could write a whole essay on Pindell’s art and practice. But this particular post is not meant to be an art review, it is meant to be about poor little me and my lonely Sunday revelations, dammit! I do, however, encourage you to read more about Pindell if you are interested— or ask me more about her. She is an artist that has escaped or been misinterpreted by the confining structure of art history until far too recently.

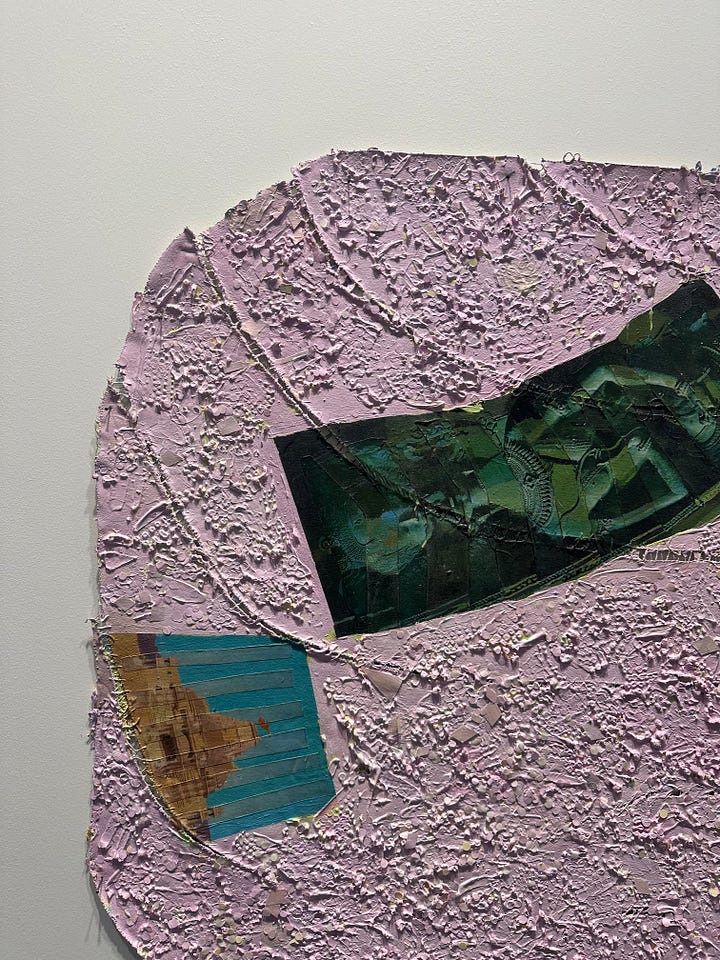

Anyway, on this particular Sunday, I found myself especially drawn to one of Pindell’s paintings titled Autobiography: India (Shive, Ganges) from 1985. The work is built upon an asymmetrical canvas, which is cut apart and stitched back together, layered with what appear to be chips of paint and hole punches of paper, and then idiosyncratically covered with a pale pink paint— sometimes dashed with a yellow pigment— that unites the composition into a single, rugged surface that is all at once continuous and irregular. Atop this canvas are roughly chopped and obscured images, maybe some postcards, of landmarks across India.

A nearby object label informed me that this work is a part of Pindell’s “Autobiography” series, which she began after a nearly fatal car crash in 1979 where she sustained memory loss. In the series, Pindell began exploring the destruction and reconstruction of memories by piecing together both literal and figurative fragments of her past. During this period of art making, the artist sharply transitioned from earlier explorations of the uniform grid structure to instead adopt her materiality into swirling mazes of uneven canvas built out of found objects. The works feel like a culmination of her constant back and forth between abstraction and figuration; a literal re-tracing of lost memories including travels through the countries and cultures of places such as India, for example, adjacent to an emblematic quest to understand how memories are formed and nurtured. The canvas I gazed upon in particular seemed to provide a space to exist outside of binaries: outside what is true or false, known or unknown, abstract or representational. A space to sit with uncertainty.

Pindell’s work is about collecting memories. I guess you could say that most artists’ practices seek to collect and reconcile with memories in one way or another. But Pindell's Autobiography series literally explores what it means to to remember and to forget. What we choose to remember and what we choose to forget. What sticks with us and why. How that process can sometimes take unexpected turns. How memory making is ambiguous.

I suppose, in some ways, I am here in Dublin to collect memories. To say yes to everything and to take risks so that, one day, I can tell my children about that time my roommate and I took a day trip to Limerick without much of an agenda, and ended up on the train ride home at 6pm drinking cheap wine disguised in a San Pellegrino bottle and eating Pringles, while giggling in matching trucker hats we bought from an iconic pub in Limerick, The Lock, that loudly declared “I got Locked at The Lock.”

I want to be able to tell my children about nights like that of my twenty-sixth birthday last weekend, when I quite boldly decided to have a birthday party after only having moved to the city a month and a half prior. I want to tell them about how my roommate and I filled our apartment with familiar strangers: our Parisian neighbors who left their numbers in the building’s elevator that day looking for new friends, and who we promptly texted to invite; the two girls we met at a Richy Mitch & The Coal Miners concert earlier that week; my co-worker and her boyfriend; the sisters I met at an influencer gala at my museum who own their own fashion company; my fellow Fulbright scholars partaking in an incredible breadth of research. I want to tell my kids about how we all ended up going out to dance— how we stayed up until far too late and how we laughed so hard as an eclectic group from all different parts of the world and of the city.

I want to tell my kids about the next morning when we went on a Viking Tour— a cheesy tour of Dublin that forces you to wear Viking hats and yell “ARGH!” at the innocent public as you zoom through the city streets in a bus that is later fastened with large floaties and transformed into a “boat,” which is then driven into the water of Dublin’s canal (the cleanliness, of which, you decide to ignore) as a sassy tour guide yells facts about everything from Dublin’s Viking history to modern day triumphs. I want to tell them how my boyfriend, James (who bought the tickets thinking it would be “hilarious and informative”) was brutally hungover and in a one-horned Viking hat that made him look like a rhino. I want to tell them how I believed it when the tour guide said the bright yellow Viking Tour bus/boat inspired the Beatles smash hit “The Yellow Submarine.”

I want to tell my kids about my roommate and my Harry Potter marathon; our nights after work when the sun set by 5pm, so with not much else to do we ordered takeout and drank leftover wine from our bizarre birthday party as we formed the basis of our new friendship amidst the soothing British accents of the wizarding world. I want to tell my kids about the sip and draw night my colleague organized at a local pub near work, where we all took our turn modelling as our co-workers drew us, and how we gasped afterwards at each other's capabilities– or laughed at each other's efforts.

But if I were to paint out my life in Dublin, and include only these wonderful memories I hope to tell my kids one day, I fear that the painting would be a perfect grid of sharp edges and precise applications of paint. There would be no seams in the center and no texture. No intriguing materiality and no open-endedness for onlookers. No possibility of gray area and uncertainty. No raw moments outside of the binaries we too often rely upon to construct life. The painting would look beautiful, but it wouldn’t be a fully authentic portrayal of reality.

In past bouts of ambiguity and hardship, my wonderful therapist of five years shared with me a poem by Rumi titled “A Great Wagon.” Specifically, she directed me towards a stanza in the middle:

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I'll meet you there.

This past weekend my dad and stepmom visited. They actually left for the airport a few hours before I sat down to write this essay. We had many beautiful and memorable moments: walking through the museum I work at to see the Andy Warhol exhibition, meeting my co-worker who toured us through the museum’s permanent collection, brunch with my roommate, a tour of Trinity’s campus, beautiful dinners full of good food and good wine, live Irish music in a traditional pub, pizza from the iconic slice shop in town, walking through St. Stephen's green, and so on.

But in the wake of their departure, and in my current state of already feeling their loss as they fly back to the states and I stay back— alone but also not alone in a new but also not too new city— this is the memory I choose to hold on to from the weekend:

The three of us had just walked the iconic cliff path of Howth, a short drive outside of Dublin city center, taking in the marvellous views of the jagged coast pushed up against the bright blue Irish Sea. As we turned inland to make our way back to the train station, we found ourselves at a strange intersection in the town, off the beaten tourist path, surrounded by a few locals’ homes, and next to a little gas station shop that lacked an actual gas station— a bodega in the center of a suburban town, if you will. We bought water bottles from two teenage boys who were blasting hard rap in the otherwise empty store. We sat outside the shop at a paint-chipped picnic table, drinking our water, and transitioning between authentic conversation and comforting silence. Our shoes began to crust with the mud we had sunk into on an unmaintained part of the trail, and our socks were damp. A car stopped at the intersection and the driver proudly announced himself with a loud burp, to which my stepmom replied by tossing him a thumbs up before the light turned green and he drove away. The sun forced its way through the clouds that had unleashed a downpour earlier, and the dewy concrete around us glowed in the light. I do not remember what thoughts existed inside my head. I was not overcome with joy nor sadness. I simply was. And I felt at peace.

In this moment, I found myself in that field beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing. And this is the sort of memory I want to collect too.

I used to use think my paintings were about "memory" until I was challenged to really explain what memory meant. I did a shallow dive into theories on memory, and my takeaway was that no one really knows how it works. But if I wanted to make paintings about memory I basically had two choices: to paint the mechanics of remembering a thing (perhaps by formally describing the repetitive hazy/intermittent/hyper-focused recall process that many of us know by experience) or to paint the thing itself the closest I could approach it (imperfect, but real), letting memory work itself out on its own. The latter was far more attractive, so I had to let go of the melancholy "promise" of memory. I like this quote, from Kierkegaard: "Joy is the present tense, with the whole emphasis on the present." Thank you for writing, Allie!

I keep saying this but I think this is your best one yet! I love the idea of the space between highs and lows as being peaceful.

Reading this makes me feel peaceful and happy, so thank you!

Also shoutout to Dublin Viking Splash tours for curing my hangover.